The year just passed was not a good one for Nasdaq OMX’s flagship stock exchange. It came under attack by a tenacious competitor and saw its share of trading plummet and its margins collapse. That, in turn, set the exchange operator back two years on the revenue front. Adding insult to injury, the damage occurred during a strong year for trading volumes overall. Through November, industrywide volumes reached 2.3 trillion shares, up 12 percent from the 2 trillion shares traded in the same period in 2008.

Behind Nasdaq’s bad news was DirectEdge ECN. The market center, which revitalized itself via a change in ownership in 2008, grabbed flow from all the major exchange operators last year, including Nasdaq. It initiated a bruising price war in December 2008 that continues today.

Nasdaq reacted clumsily. It changed its pricing from one that emphasized liquidity providers to one that favored liquidity takers and then back again. Then it flip-flopped a second time. The moves did little but irritate brokers. In 2009, Nasdaq Classic’s market share across all three tapes stood at about 20 percent in mid-December, down from 28 percent in January. That’s a considerable fall from grace for the large exchange operator. Nasdaq had managed to hold onto a nearly 30 percent share after Regulation NMS fragmented trading across several marketplaces in 2007.

See Cover Story Sidebars and Chart:

Nasdaq Experiments with Price/Size

Nasdaq’s fight to hang onto its share of the pie this year forced it to take its pricing model into the red. Until July, the exchange operator was able to maintain a positive "capture," or spread between what it received from its biggest takers and paid to its biggest providers, of 1 cent per 100 shares. But starting in June, Nasdaq increased its rebate across the three tapes significantly, agreeing to pay liquidity providers a generous 29.5 cents per 100 shares.

Then, in July, Nasdaq reduced its take charge in Tape A (NYSE-listed) and Tape C (Nasdaq) securities to 27 cents, or below its rebate. The result was a negative spread of 2.5 cents per 100 shares in those two markets. (It maintained a positive half-penny spread in Tape B–mainly exchange-traded fund–shares.)

The market share war with DirectEdge has been costly. On an annualized basis, Nasdaq was set to take in about $160 million from its domestic stock trading business last year. That would be about $90 million less than it grossed in 2008. It’s just a little bit more than the exchange operator took in for 2006.

But while a setback of that magnitude is bad news, it’s not as bad as it would have been say two years ago. In Nasdaq years, 2006 was a long time ago. The Nasdaq of 2010 is a much different company. Chief executive Bob Greifeld has transformed Nasdaq through a series of acquisitions, giving it exposure to other countries, tradable products and business lines. The upshot is that domestic equities is now a lot less important to Nasdaq’s bottom line. Diversification has enabled the company to weather the storm in cash equities.

"We’re not the Nasdaq we were three years ago," Greifeld told analysts last year. "We’re a diversified business."

Change in 2008

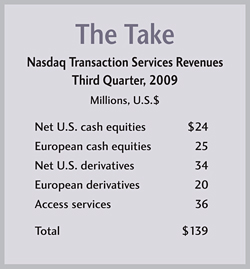

In 2006, U.S. stock trading accounted for nearly three-quarters of Nasdaq’s transactions revenues (net basis). Today, it is only one-fourth of the total. Nasdaq has expanded into stock trading in Europe and options trading in both the U.S. and Europe. It has created a profitable "co-location" business and is positioning itself to clear and trade financial instruments outside the equities space.

Everything began to change in 2008. That’s when Nasdaq merged with Sweden’s OM in a $3.7 billion transaction; launched the all-electronic Nasdaq Options Market; bought the Philadelphia Stock Exchange for $652 million; bought the Boston Stock Exchange for $61 million; and launched a multilateral trading facility (MTF) in Europe. The OM deal gave Nasdaq stock and derivatives exchanges in the Nordic countries of Sweden, Finland, Denmark and Iceland, and the Baltic countries of Lithuania, Estonia and Latvia. The MTF gives Nasdaq the rest of Europe. Nasdaq OMX Europe now trades about 1,000 European stocks and is waging a bloody battle for market share.

On the domestic options front, NOM got Nasdaq into the game, but the Philly deal made Nasdaq a serious player, giving it an automatic 16 percent market share. (Despite the exchange’s name, the Philly’s primary business was options trading.)

Today Nasdaq takes in more money from domestic options trading than it does from domestic stock trading. It takes in more money from European cash equities than from U.S. cash equities. And it takes in more money from co-location and other access services than anything else.

Because of Greifeld’s moves, the transaction services group–Nasdaq’s main engine of growth–was on track to make more money last year than it did the year before. On an annualized basis, the division stood to take in an estimated $615 million from trading last year, up from $591 million in 2008.

Diversification is both a blessing and a curse for Nasdaq. While bets on Europe and derivatives cushioned the blow last year in domestic stock trading, steady growth in these areas is far from assured. And instead of one marketplace, Nasdaq now has several to worry about. Nordic stock trading and U.S. options trading may be more profitable than U.S. cash equities, for now, but the competition is getting tougher.

Transactions services is overseen by two executive vice presidents: Eric Noll in the U.S. and Hans-Ole Jochumsen in Sweden. Noll joined Nasdaq in July after spending 15 years at institutional brokerage and market maker Susquehanna International Group, where, among his many roles, he was responsible for market center relationships. Jochumsen came up through the ranks of OM, and was previously president of Denmark’s stock exchange. His purview is Nasdaq’s Nordic Exchange, which operates the incumbent exchanges in seven countries; the largest being in Sweden.

Europe

The European stock trading business brought in $25 million in last year’s third quarter, versus $24 million for the U.S. stock trading business. It is a profitable business, and Nasdaq would like to see it stay that way. To that end, Nasdaq recently entered into a partnership with (and took a 22 percent stake in) the European Multilateral Clearing Facility to introduce centralized clearing of Nordic securities. The biggest problem facing Nasdaq in the region is the onslaught of MTFs. Unleashed by the Markets in Financial Instruments Directive, or MiFID, in 2007, to compete with Europe’s incumbent exchanges, a slew of the ECN-like platforms have popped up. Nasdaq’s Nordic Exchange has felt the impact acutely, watching its market share in the top 30 Swedish stocks, for example, drop from 100 percent to about 80 percent.

Grabbing the most share from Nasdaq is Chi-X Europe, an MTF owned by Nomura’s Instinet unit, which had 9 percent of the top 30 Swedish stocks at the end of November, according to the Fidessa Fragmentation Index. Other interlopers include Turquoise, with about 5.5 percent; BATS, with about 2 percent, and Burgundy, also with about 2 percent. Ironically, even Nasdaq’s U.K.-based MTF had 1 percent of the business.

"It’s just a matter of time before you see more volume moving away," said Olof Neiglick, Burgundy’s chief executive. Just look at what happened to the London Stock Exchange. It now has a 60 percent market share. I can’t see why competition wouldn’t work in this part of the world." Burgundy was formed by a group of Nordic banks to trade exclusively Nordic securities. A major reason behind its formation was to lower trading costs. With the combination of MTF maker-taker pricing plus centralized clearing, to which Burgundy is a party, "transaction costs can be reduced by as much as 80 percent," Neiglick said. Burgundy has reduced costs "significantly," the exec added, by instituting the maker-taker model. In contrast, Nasdaq’s Nordic and Baltic exchanges charge all comers a fee, regardless of whether they are liquidity takers or providers.

While MTFs are eating into Nasdaq Nordic’s lunch, Nasdaq’s own MTF is struggling. More than a year after launching, the pan-European platform commands only about 2 percent of the volume in the top 100 British stocks; 2 percent in the top 40 French names; and 1 percent of the top 30 German stocks. In all cases, it ranks fourth among the four major MTFs–the others are Chi-X, BATS, and Turquoise. (Chi-X, the first MTF to launch, has been an enormous success.)

Jumpball

In a bid to increase share, Nasdaq last spring offered brokers a chance to gain equity in the MTF by directing more of their volume to it. Under the plan, Nasdaq granted the brokers options on the MTF’s stock if they exceed a certain level of trades in the third quarter. Charlotte Croswell, Nasdaq OMX Europe’s chief executive, told attendees at a Reuters roundtable last May: "We’ve always said we want to get to 5 percent, but it’s a tough market. One of the reasons for doing this equity program, this ‘jumpball,’ is to boost opportunities." Noll, Croswell’s boss, notes the "program didn’t have that much uptake," but Nasdaq ended the year with a higher market share than it started.

"We have made some progress, but haven’t made nearly the kind of progress we were hoping to make," the exec said. "The MTF space in Europe is highly, highly competitive." Unlike the U.S., there is no consolidated reporting of quotes and prints. Nor is there trade-through protection. MTFs must rely on their members to direct orders to them if they are at the best price. Still, Noll is optimistic. Given the recent acquisition of the Turquoise MTF by the London Stock Exchange, Noll says "that might open up some opportunities for us in 2010."

European equities is not the only party Nasdaq has crashed with an all-electronic maker-taker offering. In March 2008, it launched its home made options market in the U.S., betting that the gradual shift to trading options in penny increments would work to its advantage. It has made steady, if unspectacular gains since, now commanding a market share of about 3 percent. However, the ongoing switchover to trading options in penny increments has not given either of the maker-taker platforms (NYSE Arca is the only other one) the big boost many in the industry expected. Only about 12 percent of their volume is in penny names, according to Tabb Group, whereas about half of all industry volume is in penny names.

That number is expected to increase to about 85 percent by this summer as the number of options classes traded in pennies increases to 363. Still, even Noll is skeptical maker-taker exchanges will see a significant boost in their share of the market. While some industry players see a 50-50 split in the near term between traditional and maker-taker exchanges, Noll’s view is more conservative. He sees maker-taker exchanges increasing their share from a current 20 percent to only 30 percent. "I don’t think it will ever overtake the traditional exchanges, but it will certainly become a more important model," Noll said.

Given the continued dominance of the traditional options exchanges and the uncertainty surrounding the viability of maker-taker, Nasdaq decided to hedge its bets. It announced its acquisition of the Philly in November 2007, about one year after announcing the launch of NOM. The acquisition in July 2008 gave Nasdaq an instant market share of about 15.5 percent. It has subsequently grown that share to 19 percent.

Based on Nasdaq’s financial data, the options business is very profitable, especially when compared to cash equities. In the first nine months of last year, Nasdaq’s U.S. derivatives business netted $104 million on $171 million in gross revenues. That’s a margin of 61 percent. By contrast, its U.S. cash equities business, during the same period, netted $121 million on $1.5 billion in revenues. That’s a margin of 8 percent.

Distinct Threat

Dark clouds are forming, however. To goose its market share in options, NYSE Euronext is in the process of selling a "significant" stake in NYSE Amex Options to a group of seven large brokers. The deal could lead to the Amex introducing very aggressive pricing. Industry observers are betting the firms will divert their flow from the Philly and other exchanges to the Amex whenever possible.

"This is a distinct threat to Nasdaq’s marketshare," said Steve Brodsky, a managing director with Chicago private equity firm Vernon & Park, and former president of CHX Holdings, parent company of the Chicago Stock Exchange. "Wherever their order flow was resident before the transaction, there is always the risk that it can move."

Four of the seven brokerages investing in Amex were part of the consortium of brokerages that invested in the Philly in 2005 and, with their order flow, propelled the Philly to a respectable 15 percent market share.

Amex’s market share has been sliding for years, although it has rebounded recently to nearly 10 percent. Many believe the deal–not yet closed as Traders Magazine was going to press–is responsible for the uplift. NYSE Euronext bought the exchange primarily for its options business a year ago. The exchange operator is selling part of it "to expand the market opportunity by lowering trading costs and to stabilize the economics of the business," analysts at William Blair contend. "The potentially biggest losers would be the traditional market structure players, including the PHLX," they added.

Noll acknowledges the threat. "Does the Amex remutualization represent a challenge to our options business?" he asked rhetorically. "Clearly. It is something we are going to have to manage with both the Philly and NOM to remain competitive."

Despite the promise surrounding new ventures, Nasdaq is certainly not giving up on the domestic cash equities business. It has two other stock exchange licenses besides the one under which it operates Nasdaq Classic, and it is making use of them.

Already providing some bang for Nasdaq’s buck is the relatively new Nasdaq OMX BX, the former Boston Stock Exchange. Nasdaq closed on the deal to buy the Boston in early 2008, and by the end of the year had reopened it as a complement to the main market center. Rather than appeal to liquidity providers by competing on the level of its rebate, Nasdaq positioned BX as a cheap place to take liquidity. BX had one of the lowest take rates in the industry.

By March of last year, however, Nasdaq decided BX’s pricing wasn’t aggressive enough. It eliminated its 20 cent take charge and actually began paying traders who took liquidity 6 cents per 100 shares. The move was unheard of. As part of the new pricing strategy, Nasdaq eliminated the BX rebate. The upshot is, Nasdaq got a negative spread of 6 cents.

Top of the Tables

To a large extent, the move to loss-leader pricing was a competitive swipe at DirectEdge’s EDGA ECN, which is also geared to liquidity takers. At the time, EDGA paid no rebate and charged no fee. In addition, Nasdaq told Traders Magazine that the move was partly intended to attract flow from dark pools. Many traders route their orders to dark pools first in hopes of finding a match and avoiding exchange fees. By eliminating the take charge, Nasdaq hoped to win them back.

The idea behind BX’s new pricing was to encourage traders to put BX at the top of their routing tables. In theory, that would, in turn, encourage liquidity providers to post on BX since they knew their order would be first in line.

In market-share terms, the plan has been a success. In early December, BX commanded about 3.5 percent of all trading. Its good fortune has been most pronounced in Tape A, or NYSE-listed, securities, where it has a 4.5 percent share.

Whatever the case, BX is now running neck and neck with EDGA. Nasdaq’s gain has forced the ECN operator to get more aggressive with its pricing as well. In November, DirectEdge started paying liquidity takers 2 cents per 100 shares, pushing its spread into the red.

The win has allowed Nasdaq to claw back some of the share Nasdaq Classic lost to DirectEdge, giving Nasdaq a combined market share of 24.5 percent. "It’s not for everybody," Noll said. "It’s not going to overtake the main market, by any means. But we’ve been able to segment the marketplace in a way that appeals to a certain type of trader."

Retrofitting the Boston Stock Exchange to appeal to a certain segment of the market has been a win for Nasdaq. It hopes for similar success with Nasdaq OMX PHLX, a new exchange it intends to launch this year using the stock exchange license it acquired when it bought the Philly.

The new bourse, if approved by the Securities and Exchange Commission, will substitute the traditional price-time priority model with one based on price and size. It will reward those traders who post the most size, rather than those who post first. At a given price point, fills will be allocated to traders in direct relation to the number of shares they post. By guaranteeing a bigger share of any incoming order, Nasdaq hopes to win back some of those traders who have abandoned the public markets in recent years as execution sizes plummeted.

Nasdaq’s segmentation (fragmentation?) of the equities marketplace with its BX and PHLX initiatives reflect the fact that domestic stock trading has become a commoditized business with low barriers to entry. Survival is based on cut-to-the-bone pricing. Thus the search for greener pastures overseas and in other asset classes.

Certainly, the transformation has been dramatic. In early 2008, Nasdaq was, as Greifeld said last year, "a pure U.S. cash equities exchange. And although we were the largest cash equity exchange in the U.S., our business didn’t reach beyond these borders. Today, we operate 17 markets, eight clearing houses around the world and are diversified across many asset classes. Our company is now a global multi-asset exchange company."

(c) 2010 Traders Magazine and SourceMedia, Inc. All Rights Reserved.

http://www.tradersmagazine.com http://www.sourcemedia.com/