ETFs: the original innovation

When State Street launched the SPDR S&P 500 exchange traded fund (ETF) in 1993 it would mark the beginning one of the most innovative disruptions on Wall St. ETFs offered the ability to trade a diverse basket of stocks, through a single exchange traded vehicle on an intraday basis. While the idea itself was not new (Canada had already launched an ETF at few years prior and the indexing mutual funds had been around for awhile), the SPY ETF was so simple and easy to own. This was a time when the internet was still new and most investors were used to brokerage accounts that required a phone call and had ticket charges of $15. The ability to click a button and be able to own a proportional share of the S&P 500 in a matter of seconds with low dollar amounts and low transaction costs was a big deal for retail investors.

To say it was revolutionary is an understatement. The cheap and easy diversification afforded by ETFs democratized the investing landscape for investors. This ushered in an entirely new era of investing which would, not only reduce costs, but also change the perspective of how many would think about investing. More and more investors would begin to think about investing in exposures and not just individual companies. For these reasons, ETFs were as much a technological innovation as a financial one.

The ETF Revolution and the Rise of Passive

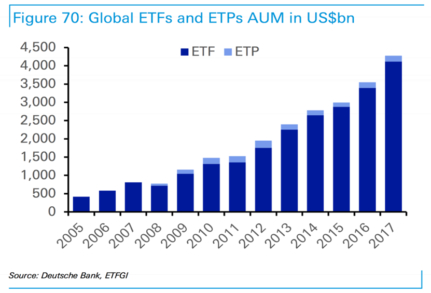

The utility of ETFs was immediately obvious and as investors continued to crave the easy diversification provided by these low-cost, transparent vehicles, Wall St. was eager to fill that demand. This saw a multi-decade period of proliferation as ETF sponsors realized there was demand for almost any kind of ETF. Everything from industry sectors to gold mining companies to the various iterations of Smart Beta ETFs had a buyer. The 2008 financial crisis only accelerated this demand as ability of active managers to deliver alpha was called into question en masse. Research even showed that active managers actually added negative alpha during the 2008 crisis[1]. Whatever the reason, 2008 proved a powerful catalyst in the growth of ETFs. As can be seen in a recent Deutche Bank report, the growth in ETFs (and ETPs[2]) since 2008 has been nothing short of extraordinary:

ETFs: Enabling the Robos

One important outcome of ETFs wasnt just that they provided investors with an inexpensive and easy way to diversify, but, that they allowed investors to think differently about how they approach the investing problem. If one could now buy exposure to various exposures (factors) as easily as they could buy stocks (including intraday liquidity), the opportunity set for portfolio construction expands dramatically. The idea of investing in various factors certainly wasnt new but, now that the practical limitations of implementing increasingly sophisticated combinations of factors was significantly reduced, it opened up a whole new world. This reality coupled with increasing academic and empirical evidence that active managers couldnt beat passive fueled the rise of so-called Robo-Advisors. Robo Advisors apply systematic, rules-based methodologies to create passive portfolios of ETFs. The goal is a low-cost, rules-based portfolio of ETFs that doesnt suffer from any of the behavioral drags on performance associated with active management.

This should be all good for investors, right? The answer is generally Yes (at least when compared to the decades past), however a couple of key issues remain. The first being with the ETFs themselves.

The Challenges of ETFs

There are now more than 2000 ETFs listed in the US which collectively account for about 30 per cent of all US trading by value, and 23 per cent by share volume.[3] Prudent investors are now asking if this is simply too many.

Quantity over Quality

With the explosion in number of ETFs, one cant help but ask if this has come at the expense of quality. Do investors really need 2000 ETFs? One has to wonder if the ETF market has become flooded with mediocre products in a business that rewards those products with the broadest appeal and quickest time to market. An increasing number of ETFs have been launched and closed within the same year. Launching an ETF is still a costly endeavor that requires several months to launch and then typically needs $50M to breakeven[4]. This fact, combined with the increasing competition in the space (which is decreasing ETF fees for the sponsors) means ETF sponsors are increasingly incentivized to launch ETFs that can capitalize on the next new thing with broad marketing appeal but not necessarily the thoughtful construction investors are relying on. With most of the focus on fees, investors risk losing sight of the importance of construction.

Liquidity

Another important concern is around ETF liquidity…and whether or not its falling victim to its own success? In a recent interview with Business Insider, Peter Dixon (Economist with Commerzbank) said: If everybody is trying to get out at the same time, the question has to be, do ETFs exacerbate or magnify the impact of the decline?[5]. A recent Bank of America Merrill Lynch report issues a similar warning about the surge in ETF popularity creating distortions in the underlying stocks.[6] As more and more investors turn towards ETFs instead of stocks for equity exposure the odds increase that the daily trading volume in the ETFs will actually be greater than their underlyings. A report last year from the Federal Reserve noted As ETFs may appear to offer greater liquidity than the markets in which they transact, their growth heightens the potential for a forced sale in the underlying markets,[7]. While this risk is most obvious for ETFs of fixed income products, it can present huge problems for equity ETFs as well. Particularly as ETFs co-mingle capital from different market participants with different timeframes, sophistication and trading capabilities, the risk of a divergence between an ETFs implied and actual liquidity becomes acute.

On Aug. 24, 2015, this risk became real when concerns from a selloff in overseas markets triggered trading halts in eight S&P 500 stocks which led to a liquidity traffic jam for 42% of all U.S. equity ETFs. In one example, the price of the Vanguard Consumer Staples ETF (VDC) fell more than 30% while the underlying holdings only dropped 9%[8],[9]. ETFs typically represent one-third of the total trading halts on any given day. On Aug. 24, ETFs accounted for 78% of total halts. This event highlighted the fact that the ETF investor is exposed to two layers of liquidity risk as the ETF itself presents its own liquidity chokepoint. This risk can have a much greater negative impact than had the investor simply owned the shares directly.

Tax Benefits

The final issue with ETFs that most investors generally dont think about is around taxes. ETFs are generally thought to be tax-efficient because, relative to mutual funds, they generally dont trade as often and therefore typically distribute less in capital gains. While this may be true, it ignores one important limitation of ETFs…the ability to tax loss harvest individual stocks.

Tax loss harvesting takes advantage of diversified portfolios of equities by selling stocks that have declined (therefore generating a tax loss) and using that loss to offset other gains. Because the stocks that have been sold can be replaced with highly correlated substitutes, the investor can theoretically maintain the portfolios return profile while harvesting the losses therefore creating a higher after-tax return. For taxable portfolios, these savings can add up quickly. Depending on the tax bracket, the benefit can be more than 1% per year.[10]

For these reasons, institutions have largely avoided the ETF structure and owned indexes directly. The size advantage of institutions has allowed them to own the individual stocks of their preferred index. Technology has no made that possible for investors of almost any size.

Direct Indexing: The Next (R)Evolution

As is the case with any industry, Finance has evolved from technological improvements over the decades. Direct Indexing is the next evolution in the investing landscape. Direct Indexing is a technology that gives investors the ability to invest directly into indices without going through the ETF structure. The technology enables investors (and advisors) to instantly create, execute in the market and manage any number of indices. In the same way as an ETF baskets of stocks are bought and sold, but with the added benefits of:

Avoiding the potential liquidity chokepoint of the ETF structure.

The ability to tax-loss harvest individual positions (because all stocks are owned directly).

The ability to create and customize any exposure (as opposed to relying on an off the shelf ETF).

Consider the following example of direct indexing, which not only highlights the benefits for the investor, but also demonstrates the added value an Advisor can provide it clients:

An advisor has several clients (ranging in account size from $1M to $100M) each of whom is invested in a slightly different Large Cap Value index tailored specifically to suit them. For instance, one client has an ESG filter while another has a cap on Utilities. Each clients exposure, in addition to being customized, is also rebalanced according to how it fits within the rest of their portfolio and tax-loss harvested in order to maximize performance based on their specific situation.

Like all innovations, Direct Indexing leverages the best of previous 1.0 technologies (in this case ETFs and robo-advisors) to create a 2.0 solution that improves efficiency, should lower costs, increases flexibility, saves time and most importantly empowers investors and advisors like never before.

[2] Exchange Traded Products (ETPs) more broadly refers to both Exchange Traded Funds (ETFs) and Exchange Traded Notes (ETNs)

[6] https://www.marketwatch.com/story/bofa-warns-the-rise-of-etfs-is-distorting-the-stock-market-2017-07-05

[8] http://www.investmentnews.com/article/20160710/FREE/307109998/etf-liquidity-a-growing-point-of-financial-industry-contention