Senator Levin, just hold on a sec. Payment for Order Flow, as a market pricing schema might not be as bad as you think.

That’s the opinion of market structure expert Larry Tabb, founder and CEO of capital markets research and consulting firm TABB Group. Tabb wrote a letter to U.S. Senator Carl Levin, chairman of the Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, disagreeing with conclusions Levin shared in his July 15th letter to SEC Chair Mary Jo White, asking that she ban payment for order flow:

“Such payments create another incentive for brokers to maximize their own profits at the expense of best execution of customer orders,” Tabb wrote. “In addition, while retail brokers must disclose the amount they receive per-share from wholesale brokers for order flow, the aggregate totals of such payments are typically not disclosed. As a result, in most cases, consumers are unaware that the fractions of a cent received by retail brokers per-share add up to a multi-million dollar conflict of interest. Furthermore, the limited disclosures currently required are not filed with the SEC and often disappear from broker web sites at the end of each quarter.”

Also in the letter, dated August 11th, Tabb explained that banning this practice would be a serious mistake, that “we need more disclosure on payments for order flow arrangements; reports should be filed with the SEC; better archival mechanisms are needed; and current reporting requirements are not as informative as needed. However, I would pause between requiring more transparency and the attempt to ban the practice. While payment for order flow does introduce conflicts, banning the practice will only create more challenges and magnify conflicts of interest.”

He proceeded to give three reasons why retail investors’ orders are valuable, that paring size, spreads and the herding nature of institutions, create an environment in which interacting with smaller retail investors is safer for a market maker than providing institutional liquidity.

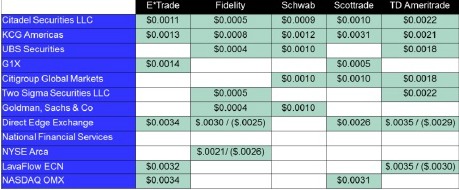

Referring the senator to “U.S. Equity Market Structure: Q1-2014 Market Metrics,” a July 2014 TABB report that aggregates and publishes price improvement statistics, he says while it’s in the best interest of retail brokers to obtain as much payment for their order flow, they also force wholesalers to actively compete on their price improvement statistics, adding that although this is not a perfect process, “it’s transparent, aboveboard and many retail investors receive a better price than offered in the market.”

Given the SEC’s desire to ensure retail investors obtain price improvement, he concludes, payment for order flow allows brokers to reduce retail commissions, invest in better client-facing technology and provide a better customer-facing environment. The process is transparent and regulated (although more rigorous reporting would absolutely be welcomed). It allows wholesalers to not only compete over who pays the broker the most, but to compete over the benefits provided to retail clients. While not perfect, it works without drastically layering on a new set of costs, conflicts, management challenges and potential under-the-table incentives. “Payment for order flow also provides retail brokers with investment capital to spawn innovation; it creates a market where wholesalers actively compete to provide top-tier execution; it levels the execution framework for individuals, given their inability to invest in professional trading technology; and most important, it provides a better execution experience for clients.”

Below is the complete letter from Tabb to Levin:

The Honorable Carl Levin

US Senator and

Chairman, Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations

269 Russell Office Building

U.S. Senate

Washington, DC 20510-2202

August 11, 2014

Dear Senator Levin:

I read with interest your letter to SEC Chair White dated July 15, 2014 and while I understand your sentiments, I am generally not in agreement with your conclusions, especially with regards to your thoughts on Payment for Order Flow.

Toward the end of your letter you state in your discussion of payment for order flow:

“Such payments create another incentive for brokers to maximize their own profits at the expense of best execution of customer orders. In addition, while retail brokers must disclose the amount they receive per-share from wholesale brokers for order flow, the aggregate totals of such payments are typically not disclosed. As a result, in most cases, consumers are unaware that the fractions of a cent received by retail brokers per-share add up to a multi-million-dollar conflict of interest. Furthermore, the limited disclosures currently required are not filed with the SEC and often disappear from broker web sites at the end of each quarter.”

I completely agree with you that:

. We need more disclosure on payment for order flow arrangements.

. Reports should not be filed with the SEC.

. Better archival mechanisms are needed, and

. Current reporting requirements are not as informative as needed.

However, I would pause between requiring more transparency and the attempt to ban the practice.

While payment for order flow does introduce conflicts, banning the practices will only create more challenges, and magnify conflicts of interest.

No matter how bad payment for order flow sounds, payment for order flow is a legitimate practice governed by the SEC. Orders must be priced at least as well as the national best bid offer (NBBO), and all executions are covered by best execution rules, which require brokers to execute orders at the most advantageous price to the client.

The problem with banning payment for order flow is that retail flow is valuable and just banning the practice doesn’t change the value of this order stream; rather, it changes, and possibly corrupts, how that value is harvested.

Retail investors’ orders are valuable because of three key factors: order size, the mandated width of trading spreads, and the herding nature of institutional order flow.

First, while many non-professional investors have significant financial resources, they generally do not invest with the same concentration as institutions. Since market makers are providing client liquidity (to capture a spread), large market-moving client orders more often than not do not provide enough time for intermediaries to get out of their positions before the price changes. This causes market making in these situations to become unprofitable. Non-professional orders, since they are smaller, generally do not have as much heft to move the market, allowing the market maker to unwind trades more easily and to effectively capture a larger spread. It generally is more profitable to interact with non-professional orders.

Second, mandated minimum spreads allow market makers to capture a greater amount of the economics than if markets were free to trade with no minimum spread.

Third, many institutional investors are full-time and employ professional traders who keep abreast of the latest equity research, analyst calls, and corporate management decisions, and have sophisticated investment and trading tools. Professionals are more prone to make similar trading decisions, causing them to move synchronously – i.e., to herd. Smaller investors/traders are less likely to be driven by professional information, making retail investors’ trading cycles different than professionals’.

Paring these three factors – size, spreads, and the herding nature of institutions – creates an environment in which interacting with smaller retail investors is safer for a market maker than providing institutional liquidity. Because markets don’t know when they are interacting with retail flow, spreads are artificially wide when trading against retail flow.

When non-professional marketable orders are routed directly to an exchange, the orders most likely will trade at either the best bid or offer, forcing the retail investor (using a market order) to receive the least and or pay the most. While good for the quoting party (mostly market makers or professionals), it is not good for the non-professional investor.

Payment for order flow is the tool that helps wholesalers give a portion of that benefit back to investors and retail brokers.

Now, the price improvement a retail investor may see may only be 1/10 or 2/10s of a cent ($0.001/$0.002); however, it transfers more value to retail investors than if they transacted natively on exchange.

Many think this process is too opaque; however, the SEC forces all wholesalers and exchanges to provide execution-quality reports (605/6 Reports). These reports display both brokers’ order routing policies and wholesalers’ price improvement statistics.

While it is clearly in the best interests of the retail brokers to obtain as much payment for their order flow as possible, the retail brokers also force the wholesalers to actively compete on their price improvement statistics.

Is the process perfect? Certainly not. It is, however, transparent and aboveboard. And many retail investors do receive a better price than offered in the market.

Banning payment for order flow doesn’t change the nature of the order flow. Retail flow is and will always be valuable – non-professional orders are smaller and safer to interact with, it is better for the market if spreads are restricted, and institutions herd. Banning payments forces retail brokers either to set up their own trading desks, harvest value directly, or send valuable order flow to wholesalers/brokers that now are not allowed to pay for it.

Setting up a trading desk that provides wholesaler-quality execution is expensive. People, technology, data, and infrastructure are complicated and costly, and not investing in trading infrastructure opens up firms to best execution criticism.

Bringing the process in-house makes it harder to manage, as the flow becomes less portable and competition to maximize the value of that flow declines, and since different markets have different pricing structures, there will continue to be agency conflicts, as orders could still be routed to exchanges providing the highest rebates and charging the lowest fees.

Creating a competitive process typically is better than managing an internal process, especially for a high-fixed-cost, low-variable-cost operation such as building a trading desk.

Trading valuable retail flows in-house also could create an environment rife for corruption. Taking a multimillion-dollar asset (order flow stream) and turning it into a cost will most certainly create incentives for non-transparent influencing mechanisms. Policing this would certainly become problematic.

Since the SEC’s decision to facilitate a better environment for retail execution led to the development of payment for order flow, the practice has been called controversial, at best, and nefarious, at worst. In my view, payment for order flow, while conflict-laden, is not as conflict-laden as other execution means and provides a positive outcome for retail investors, their brokers, and the concentrating wholesalers.

Given the SEC’s desire to ensure retail investors obtain price improvement, payment for order flow allows brokers to reduce retail commissions, invest in better client-facing technology, and provide a better customer-facing environment. The process is transparent and regulated (although more rigorous reporting would absolutely be welcomed). It allows wholesalers not only to compete over who pays the broker the most, but to compete over the benefits provided to retail clients.

While this is not perfect, it works – without drastically layering on a new set of costs, conflicts, management challenges, and potential under-the-table incentives. Payment for order flow also provides retail brokers with investment capital to spawn innovation; it creates a market where wholesalers actively compete to provide top-tier execution; it levels the execution framework for individuals, given their inability to invest in professional trading technology; and most important, it provides a better execution experience for clients.

In my position as a market structure expert and the CEO of a financial markets research firm, banning this practice would be a serious mistake.

I would like to thank you for your patience in taking my thoughts into consideration.

Regards,

Larry Tabb

Founder & CEO

TABB Group

cc. The Honorable Mary Jo White

Chair, Securities and Exchange Commission

I 00 F Street, NE

Washington, DC 20549