Whether or not a single large order caused the "flash crash" in May 2010, as the Securities and Exchange Commission has alleged, brokers are under pressure to make sure they don’t toss any oversize or out-of-control orders into the market.

A recent report produced by a joint advisory committee of the SEC and the Commodity Futures Trading Commission urged the SEC to work with the Financial Industry Regulatory Authority and the exchanges "to develop effective testing of sponsoring broker-dealer risk management controls and supervisory procedures."

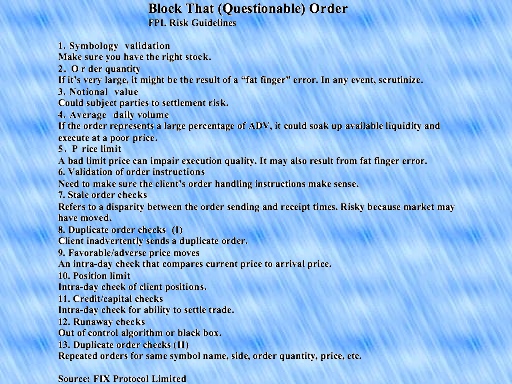

The concern from Washington prompted a group of 12 brokerages to collaborate on a set of risk guidelines intended for adoption across the industry. Working under the aegis of FIX Protocol Limited, the group recently published a checklist of 13 risk controls it hopes will deter the acceptance of orders that might disrupt the marketplace.

FIX Protocol is a pan-industry group that promotes and supports electronic trading through the ubiquitous FIX communications standard. The guidelines devised by the members of the FPL Risk Management Working Group focus strictly on algorithmic and direct-market-access orders for cash equities. The members include the nine largest trading firms, which account for the vast majority of industry orders.

The hope of those involved in the FPL initiative is that the guidelines will represent the gold standard of order handling. Those broker-dealers that adhere to the guidelines would be deemed best in class, and would, presumably, stand out in the eyes of the buyside.

Pressure from the money managers would eventually force all brokers to adopt the guidelines, which would reduce the likelihood of disruptive orders making their way into the markets. Such an industry-based solution would, in turn, make the SEC happy, and perhaps forestall any new rules the regulator was considering.

That may be wishful thinking. Although there is a good chance the guidelines will be accepted by brokers–they already have similar checks in place–the SEC may want even more. Some sources say the guidelines lack teeth and are unlikely to dissuade the SEC from taking action.

Sources tell Traders Magazine that some committee members wanted the brokers to incorporate hard numbers into the guidelines. One possibility was automatically rejecting orders with a notional value of at least $500 million. Another was to reject any single order equal to 10 percent of the security’s average daily volume. This idea of hard numbers, however, didn’t fly with others, who protested that it would reduce their flexibility.

"Unfortunately, there was almost universal push-back on that," one committee member said. "They said, ‘We need the freedom to up those numbers when it makes sense.’ Because of the push-back, this has become just a rough framework. I don’t think the SEC will accept this."

Indeed, much of the discord among the FPL group centered around whether any orders should be automatically rejected. In the end, the committee agreed that larger orders that exceeded predetermined risk levels would be "paused" or routed to a sales trader who could exercise judgment. Rejecting an algo order outright was deemed an unfavorable outcome, some said, and could undermine all the hard work put into winning the client in the first place. The risk was that the customer would simply send the order to another broker.

"There was a lot of controversy around what to do with an order that exceeded a given risk threshold," said Neal Goldstein, a managing director at Nomura Securities, and co-chair of the FPL committee. "Some felt it should be rejected outright. But ultimately we agreed that inadvertently rejecting a legitimate order has adverse implications for both the buyside client and the broker."

Under the guidelines, the decision to reject or pause an order depends on the nature of the order. Algorithmic orders that will be executed over a relatively long period of time can be paused. Smaller, low-latency orders that may run through co-location facilities should be rejected outright.

The FPL committee was formed last year in the wake of the flash crash. Driving the effort was the SEC’s conclusion that the market flip-flop was caused by a mutual fund dumping 75,000 eMini futures contracts, worth $4.1 billion, into the market in the space of 20 minutes.

The SEC has signaled it could introduce new rules to force brokers to take more responsibility to prevent such occurrences in the future. It has already taken steps to eliminate so-called "naked sponsored access," with Rule 15c3-5. Naked access involves brokers renting their exchange memberships to traders without risk-checking their orders.

The joint SEC-CFTC advisory committee applauded the SEC’s move with Rule 15c3-5, but still wants the regulator to go further. It also applauded recent CFTC moves to consider specifying "as a disruptive trading practice the disorderly execution of particularly large orders."

While the FPL risk checks are meant to protect the market and the brokerages from several types of problem orders (see table), the primary focus is on excessively large orders. Those are measured by their quantity, notional value or percentage of average daily volume.

The FPL guidelines have their limits. While they urge brokers to take into account a client’s positions, they do so only with regard to the security currently being traded–a stock. The guidelines don’t require brokers to aggregate a client’s total positions across the firm. The scope of the checklist is limited to the algorithmic or direct-market-access trading of cash equities. It does not consider other asset classes or departments within a firm, such as program trading or derivatives.

As such, the guidelines may not go far enough for the SEC. The regulator’s Division of Trading and Markets is said to be making enquiries as to whether brokers can aggregate client position risk across all departments. The ability to calculate instantaneously a client’s positions across multiple trading desks and asset classes would be beneficial, Goldstein said, but extremely costly and difficult to implement.

"To really quantify and manage counter party risk you need to have–at any moment–a snapshot of a client’s total position," he said. "But this would be a challenge for many brokers with legacy platforms."

The early hope of some on the FPL committee was that the term "FPL certified" would carry the same weight as the "UL" nomenclature. United Laboratories is the well-known, not-for-profit product safety testing and certification organization that has been operating for more than a century.

But that is looking unlikely, Goldstein said. "It became apparent fairly quickly that coming up with some oversight or impartial arbitrator to expedite that would be very challenging and costly," he said. "The reality is that it would be very difficult to apply enforcement."